Planning Adviser Dr Wahiduddin Mahmud has said that the government’s sweeping overhaul of the public procurement system has temporarily slowed down the implementation of the Annual Development Programme (ADP), but the reforms are crucial to dismantling entrenched contractor monopolies and improving transparency in public projects.

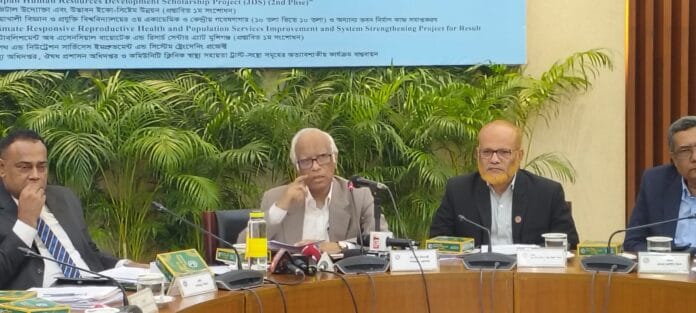

Briefing reporters after the ECNEC meeting on Monday, Dr Mahmud acknowledged that ADP implementation “has not become dynamic” despite continuous efforts.

“The old problems are still there,” he said. “The biggest challenge is that people are now reluctant to take on the role of project director, and contractors are no longer showing the same level of enthusiasm as before.”

He attributed this hesitation largely to the Public Procurement Policy 2025, which introduces far stricter transparency requirements. According to him, the previous system allowed a handful of influential contractors to dominate major infrastructure projects, from highways to railways.

“The evaluation process was shaped in a way that ensured the same parties kept winning contracts,” he said.

Dr Mahmud described the new policy as a “major reform” that makes anonymity and proxy contracting impossible.

“No one can take a contract under someone else’s name. Anyone securing a contract must disclose full information about their businesses, tax records, and affiliated entities. Everything must be open,” he said, adding that these requirements have made the environment tougher for habitual contractors.

To diversify participation, the government has also introduced provisions allowing new and young entrepreneurs—including those without prior experience—to join large tenders as minor partners.

“We can’t let the same contractors dominate forever,” he said. “Those who do business honestly and pay taxes deserve opportunities. The younger generation must be given space.”

He noted that the new fully digital, end-to-end evaluation system—implemented from the upazila level to the highest purchasing committees—is another reason behind the slowdown, particularly in large procurement decisions.

“They will have to learn. That’s why there is some delay,” he said.

The adviser also highlighted operational challenges at the local level, where upazila and district councils—currently managed entirely by government officials—are responsible for numerous projects but lack adequate time for supervision.

To improve oversight, ECNEC has recently attached strict mandatory conditions to all newly approved locally implemented projects, particularly those under LGED. One major requirement is institutionalised community monitoring, ensuring beneficiaries and local residents actively oversee project quality.

“People living in the area know best whether the road, bridge, or construction is being done properly. They should be able to resist poor-quality work,” he said.

Project sites will also be required to display publicly accessible information, including total cost, implementation progress, contractor identity, and details of materials used. Dr Mahmud recalled that similar disclosure practices were introduced during the late 1990s when he previously served in government, “but after some time everyone forgets.”

He stressed that transparency, community participation, and strict monitoring are indispensable as the country seeks to create employment and accelerate development through local-level projects.